“I understood the world and the people much better, through my long journey with cinema”

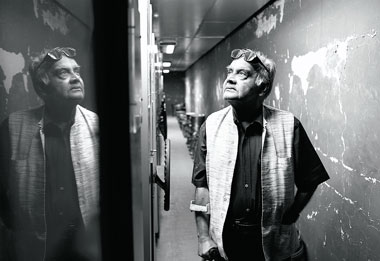

So P.K. Nair describes his relationship with cinema at the beginning of Shivendra Singh Dungarpur’s marvellous film, Celluloid Man (2012). Three years in the making, Dungarpur’s portrait of the legendary film archivist brings together stories from colleagues, filmmakers, students, friends and family, alongside the many hours spent interviewing Nair himself at home in Pune and at the National Film Archive of India, where he dedicated his life to preserving the prints that comprised India’s film heritage. Countless contributions from those influenced and inspired by Nair, assert his importance as a figure that worked tirelessly to ensure that cinema in India and the world would be preserved and that a passion and knowledge of filmmaking would be passed on to each new generation.

Dungarpur is himself the founder of the Film Heritage Foundation, which exists to support the conservation, preservation and restoration of the moving image, and having studied at the Film and Television Institute of India, he recognised Nair’s vital position at the centre of preserving film in India. The result of the director’s persistence in creating a portrait of Nair, is a film overflowing with insight, wit and enthusiasm for cinema, not just as a form of storytelling or art, but in its very physicality, as reels and cans are shown and discussed with enduring reverence.

Perhaps what is most fascinating – and poignant considering the digital age of exchange and sharing via download and streaming – are the stories relating to Nair’s acquisition of prints for the archive. Nair recalls that dozens of Russian films were donated, among them Battleship Potemkin and Alexander Nevsky, with no request for payment made; there’s also a story that he exchanged Pather Panchali for The Battle of Algiers and later Sant Tukaram for Hitchcock’s Blackmail with the British Film Institute. To hear of the exchange these films, told casually as though such traffic of prints is effortless, gives the impression that the creation of an archive is much like any process of collecting – where a community of enthusiasts survey their acquisitions for trading much like records, or marbles or cards. Yet Nair’s archive of prints were not kept hidden away – though it might be assumed that their preciousness would make them inaccessible to the public or students – instead we hear of how they were seen and used by everyone from eminent filmmakers to the villagers of Pune, as a nut farmer and a retired school teacher each recall fondly the pleasure of seeing Rashomon and Pather Panchali.

Perhaps what is most fascinating – and poignant considering the digital age of exchange and sharing via download and streaming – are the stories relating to Nair’s acquisition of prints for the archive. Nair recalls that dozens of Russian films were donated, among them Battleship Potemkin and Alexander Nevsky, with no request for payment made; there’s also a story that he exchanged Pather Panchali for The Battle of Algiers and later Sant Tukaram for Hitchcock’s Blackmail with the British Film Institute. To hear of the exchange these films, told casually as though such traffic of prints is effortless, gives the impression that the creation of an archive is much like any process of collecting – where a community of enthusiasts survey their acquisitions for trading much like records, or marbles or cards. Yet Nair’s archive of prints were not kept hidden away – though it might be assumed that their preciousness would make them inaccessible to the public or students – instead we hear of how they were seen and used by everyone from eminent filmmakers to the villagers of Pune, as a nut farmer and a retired school teacher each recall fondly the pleasure of seeing Rashomon and Pather Panchali.

Dungarpur also interviewed Nair’s daughter, Beena, and it’s her recollection of childhood that is the most revealing aspect of Celluloid Man. To have dedicated so much of his life to cinema – complying with requests to view films even at 3am – it becomes apparent through Beena’s description that her father was not present in the home when she and her siblings were growing up. We hear that he would look forward to work, stay Iong hours and “not show any interest at all” in matters of the family. Beena describes how only when they matured, did they find common ground with their father and become close, developing the friendship that they cherish today. It’s in this testimony of the sacrifice of family life that one understands how dedicated Nair was to his work, confirmed in a later scene in which he describes moving back to Pune from Tivandrum following his wife’s passing because he felt that he must always be close to the film institute, recognising the archive as his true progeny.

“I think a person’s lifetime is too short a period to save all of the world’s film heritage,” so declares Nair, almost regretfully toward the end of Celluloid Man. Nevertheless it becomes apparent that this was his attempt, and in the appreciation of his peers and the audiences of the archive’s screenings, and of course Dungarpur’s own endeavour to document them, is evidence that his efforts have been appreciated, even if there will never be a person with the equivalent drive to continue his work.

A lasting image in Celluloid Man is that of Nair standing in front of the cinema screen quoting Citizen Kane as is its flickering image is projected behind him, framing his ageing stature. Here, Dungarpur presents Nair just as French archivist Henri Langlois is shown in Phantom of the Cinémathèque (Jacques Richard, 2004), standing before the cinema screen, describing how he wanted to show “shadows of the living coexisting with shadows of the dead.” Through Dungarpur’s carefully constructed portrait, this image reveals both men almost as if they have achieved that goal – of being immersed in cinema, of becoming inseparable from that which they love through the relentless activity of preserving its memory.

A lasting image in Celluloid Man is that of Nair standing in front of the cinema screen quoting Citizen Kane as is its flickering image is projected behind him, framing his ageing stature. Here, Dungarpur presents Nair just as French archivist Henri Langlois is shown in Phantom of the Cinémathèque (Jacques Richard, 2004), standing before the cinema screen, describing how he wanted to show “shadows of the living coexisting with shadows of the dead.” Through Dungarpur’s carefully constructed portrait, this image reveals both men almost as if they have achieved that goal – of being immersed in cinema, of becoming inseparable from that which they love through the relentless activity of preserving its memory.

Celluloid Man is released by Second Run DVD and as ever, the accompanying special features are a treasure in themselves. An appreciation by filmmaker Mark Cousins demonstrates the reverence for P.K. Nair and the act of archiving to international film culture, whilst interviews and extracts from Dungarpur’s production diary are steeped in all the detail of realising the project, of particular pleasure – discovering the efforts made to ensure that the film could be shot on film, not digital – with a document of the ever decreasing stock of 16mm, which thankfully lasted to produce the gorgeous footage that truly does justice to the film’s subject.