Do you know the films of Apichatpong Weerasethakul? Lucky if you do, for his films seem to offer a window into a mystical world at once alike and so strange to the one we usually perceive. If you don’t I would like to take some time to describe what it is you’re missing, and why you should seek him out.

Weerasethakul (or ‘Joe’ as he introduces himself) was born in 1970 in northeast of Thailand. He studied Architecture and Fine Art and started making films and videos in the 1990’s. Working independently of the Thai studio system, Weerasethakul’s films consistently portray a world that teeters between differing planes of reality or ideas of consciousness, whilst his use of mostly non-professional actors render this otherworldliness completely natural. My own experience of discovering ‘Joe’s’ work came when I went to see his Palme D’or winning Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall his Past Lives (2010). A beguiling experience – I truly felt that in the auditorium that day I entered another reality. Uncle Boonmee was described by critics as a retrospective look at the directors past work – a ‘greatest hits’ of sorts of his most poignant ideas, but nevertheless a claim surprising for a filmmaker so young. After seeing it however, I did indeed decided to go back to the beginning, as it were, and watch Weerasethakul’s previous films to discover how his unique vision became so clear.

Rather than attempt to write about all that I’ve seen however, I’ll simply concentrate on two: Blissfully Yours (2002) and Tropical Malady (2004). Weerasethakul has described how the inspiration for Blissfully Yours came from witnessing two female illegal immigrants from Burma, being arrested at the zoo. The director wondered what kind of day the women had before the authorities brought their freedom to an end. Similarly, in the film, the character Min is a Burmese immigrant whose uncle, Sirote and his wife Orn are trying to bribe their doctor into giving him a medical certificate so that he can work. Blissfully Yours is a film of two halves – the first concentrating on the interactions these characters have with authorities and the second literally escaping from this as Min takes his Thai girlfriend, Roong to a secluded beauty spot in the jungle. The simplicity of the plot of Blissfully Yours is its strength – though some impatient viewers may find its slow pace tedious, the beauty in the imagery on display demonstrates a writer/director with a fascination for the transformative effect of nature.

The primacy of nature and human response to it is perhaps given true clarity in one scene in particular. Having driven out of town – action marked as the beginning of the second part of the film by the credits sequence appearing on screen; Roong and Min arrive at the edge of a secluded forest. Making their way through the dense jungle, the pair struggle with the heat and uneven ground until Min eventually signals Roon to stop. Telling her to cover her eyes, he leads her slowly out of the undergrowth. Before her is a magnificent panoramic view of the mountains, illuminated gently by the afternoon sun. In any mainstream epic, a scene like this (in Peter Jackson’s King Kong for example) would frame the landscape from Roong’s point of view, allowing the audience to ‘experience’ the spectacle with the character. Weerasethakul instead partially blocks the sky with his actors, and captures Roong’s expression of joy and surprise instead. It is the human reaction to nature that is interesting, and crucial to the directors understanding of life.

Weerasethakul’s understanding is partially influenced by his Buddhism, and the presence of spirits alongside the living is common throughout his films. ‘Joe’ has also continually been compared to Terrence Malick in his use of nature as a central character in his work, or as writer Adrian Martin put it, nature is ‘always beaming, breathing and pulsating at the heart of his oeuvre’ (Sight & Sound December 2010).

Blissfully Yours also demonstrates a Proustian affinity with the details of life. In his introduction to the film accompanying the DVD release, Weerasethakul speaks of developing the characters in his films from the experiences of the actors who play them. Little, seemingly insignificant actions such as the way they eat are all part of the characters search for bliss in a frustrating world. Peace perhaps comes from a combination of discovering the extraordinary and the comfort of the familiar, or preferred way of doing things. Even if as a viewer of Blissfully Yours, this seems to amount to very little so-called plot developing action, I feel that everyone can and should relate to the intention of attempting to slow down for a while and listen to oneself, as the characters do.

Tropical Malady, for its own part, begins in much the same way as the former film: with a naturalistic view of ordinary life. Army men are seen posing with a body they find next to the jungle. One of them, Keng, eats dinner with a family who live nearby. He forms an attachment with one of them, Tong, who works at an ice factory. Their relationship develops into one of tentative, then passionate love, all played out entirely naturally. They attend a pop show, have dinner, and then they visit a shrine inside a cave, signalling the introduction of the mystical to the film. The two-part structure is also adhered to in Tropical Malady. Keng and Tong, after a consummation of their love, of sorts, seem to part, with Tong walking into the darkness along the side of a road. Following this, a short film within the film signals the break between the first and second part of the film; A Spirit’s Path tells the tale of a powerful shaman who entered the jungle and took on the form of a tiger. The second half of the film concerns Keng’s search for the beast, and his eventual union with the spirit that dwells inside it. Weerasethakul draws parallel’s between the unclassifiable connection between human spirits and that of the hunter and hunted; the sounds of the jungle combined with that of radio static uncannily evocative. In one sense a horror story, Tropical Malady is daringly experimental for its use of darkness. Weerasethakul has spoken about how his intentions were to try and film at the lowest possible light levels, perhaps to emphasise that moment when illumination does occur.

What I find so involving about Apichatpong’s films, and concordantly the work of Malick, is that by focusing on nature, there seems to be an attempt to evoke through cinema, the beauty and purity of unmediated experience – which is of course impossible; it is screened from us by the frame of the film-camera and mode of spectatorship that we choose. That is not to say that media is not a presence in Joe’s work – at the end of Uncle Boonmee the characters are seen catching up on their television (and by the way, seeming to simultaneously go out for dinner) whilst in Syndromes and a Century, all the gadgets of contemporary culture are present and correct. It’s simply that more than conveying this basic experience of daily life, Weerasethakul seems to want to go beyond that into a realm that can only be felt, and on the way communicate with wry humour, some of the absurdities of human activity.

What I find so involving about Apichatpong’s films, and concordantly the work of Malick, is that by focusing on nature, there seems to be an attempt to evoke through cinema, the beauty and purity of unmediated experience – which is of course impossible; it is screened from us by the frame of the film-camera and mode of spectatorship that we choose. That is not to say that media is not a presence in Joe’s work – at the end of Uncle Boonmee the characters are seen catching up on their television (and by the way, seeming to simultaneously go out for dinner) whilst in Syndromes and a Century, all the gadgets of contemporary culture are present and correct. It’s simply that more than conveying this basic experience of daily life, Weerasethakul seems to want to go beyond that into a realm that can only be felt, and on the way communicate with wry humour, some of the absurdities of human activity.

There are so many things that I could say about this unique directors work, how his films are connected, and the characters seem to all exist within the same film-world and each narrative somehow linked to the next. His use of absurdist comedy and reflexivity are also strange pleasures to be found. I hope that you seek out these films and I invite you to share your views about Joe, and your feelings about the worlds he creates.

Blissfully Yours and Tropical Malady are distributed by Second Run DVD. For links to other distributors of Joe’s films see my blogroll.

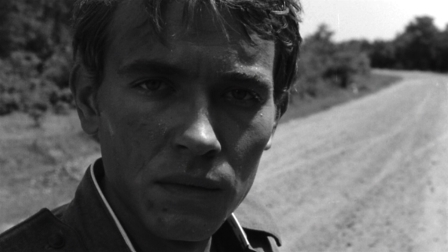

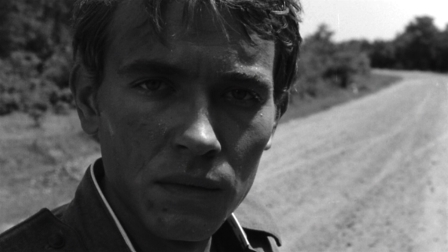

Whilst working for Edinburgh International Film Festival 2011, I had the pleasure of meeting Béla Tarr (actually ‘pleasure’ is perhaps too weak – compared to the other film related events in my life last year meeting Tarr was probably the high point). Tarr was at the festival for his own film, the incredible Turin Horse, but he was also there to introduce a selection of films he had chosen as a guest curator. One of the enigmatic directors’ selection was The Round Up (Szegénylegények, 1965) by fellow Hungarian filmmaker, Miklós Jancsó. I watched as Tarr described how highly he regarded Jancsó, and said very simply that his films were wonderful and everyone should see them. This humble introduction was all I was able to see of the screening however as my work held my attention elsewhere. Fortunately Second Run DVD re-released The Round Up in their box set The Miklós Jancsó Collection alongside My Way Home (így jöttem, 1964) and The Red and the White (Csillagosok, katonák, 1967) so Tarr’s recommendation hasn’t withered into to the ether of hundreds of other films that I intend to see and then never get around to…

Whilst working for Edinburgh International Film Festival 2011, I had the pleasure of meeting Béla Tarr (actually ‘pleasure’ is perhaps too weak – compared to the other film related events in my life last year meeting Tarr was probably the high point). Tarr was at the festival for his own film, the incredible Turin Horse, but he was also there to introduce a selection of films he had chosen as a guest curator. One of the enigmatic directors’ selection was The Round Up (Szegénylegények, 1965) by fellow Hungarian filmmaker, Miklós Jancsó. I watched as Tarr described how highly he regarded Jancsó, and said very simply that his films were wonderful and everyone should see them. This humble introduction was all I was able to see of the screening however as my work held my attention elsewhere. Fortunately Second Run DVD re-released The Round Up in their box set The Miklós Jancsó Collection alongside My Way Home (így jöttem, 1964) and The Red and the White (Csillagosok, katonák, 1967) so Tarr’s recommendation hasn’t withered into to the ether of hundreds of other films that I intend to see and then never get around to… The Red and the White is demonstrable most overtly of Jancsó as a political filmmaker. Detailing the fighting between the Hungarian volunteers who supported the ‘Red’ revolutionaries against the ‘White’ counter- revolutionaries, the film displays the wider implications of decisions made by the powerful over the weak, and how unstable and that power can be.

The Red and the White is demonstrable most overtly of Jancsó as a political filmmaker. Detailing the fighting between the Hungarian volunteers who supported the ‘Red’ revolutionaries against the ‘White’ counter- revolutionaries, the film displays the wider implications of decisions made by the powerful over the weak, and how unstable and that power can be.