Dirty Dancing was my option for a temporary break from thought at the end of the weekend’s more strenuous viewing, and I let its combination of melodrama, daddy issues, US loss of innocence and wildly anachronistic use of 80’s pop tunes wash over me with ease.

Dirty Dancing was my option for a temporary break from thought at the end of the weekend’s more strenuous viewing, and I let its combination of melodrama, daddy issues, US loss of innocence and wildly anachronistic use of 80’s pop tunes wash over me with ease.

Catching up with current releases meant a double bill consisting of Ben Affleck’s third directorial outing, the Oscar-tipped Argo, and Jacques Audiard’s latest, Rust and Bone following the highly praised A Prophet (2009). Argo stars the aforementioned actor-turned director alongside Alan Arkin, John Goodman, Brian Cranston and a selection of recognisable (though not film star) faces, including the excellent and almost unrecognisable Scoot McNairy (Monsters, In Search of a Midnight Kiss), and is based on a real CIA operation that was declassified by President Clinton in 1997.  Opening with a potted (and animated) history of how the US overthrew the democratically elected Mosaddegh government in 1953, placing a more secular Shah in its place, the film then begins proper with scenes showing the storming of the US embassy by protestors objecting to the Shah being taken in by the US, rather than be tried for his crimes against human rights. The protestors take 53 hostages, but six embassy employees escape to the Canadian ambassadors house – and this is where the great thrust of the drama comes from – how to get them out without being detected?

Opening with a potted (and animated) history of how the US overthrew the democratically elected Mosaddegh government in 1953, placing a more secular Shah in its place, the film then begins proper with scenes showing the storming of the US embassy by protestors objecting to the Shah being taken in by the US, rather than be tried for his crimes against human rights. The protestors take 53 hostages, but six embassy employees escape to the Canadian ambassadors house – and this is where the great thrust of the drama comes from – how to get them out without being detected?

What follows is Tony Mendez (Affleck), an exfiltration expert, convincing the CIA to approve an operation to remove the six ‘house guests’ by fooling the Iranian authorities into taking them for a Canadian film crew, scouting the location for a Sci-fi film called, Argo. The result of this strange but true thriller plot is a (undoubtedly entertaining) combination of Hollywood satire, political corruption and heist movie convention. What started out as quite a balanced view of the US/Iranian relationship, soon gave way to fairly ordinary jibes at the business that is Hollywood, and a thriller that turned sympathetic Iranians into threatening caricatures – a menacing, fearful Other. For a film that tells a previously untold story, I was surprised by how much I felt I’d seen it all before.

Rust and Bone on the other hand – despite perhaps deserving just as much criticism being levelled at it – succeeded in being really quite moving. The plot concerns the rehabilitation of Marion Cotillard’s Stéphanie, an orca trainer who one day loses her legs during an incident at the marine centre where she works. Reconnecting with bouncer Ali (Matthias Schoenaerts), whom she met at a club before the accident, Stéphanie gradually develops a new place in the world, at first through their casual relationship and later becoming a deeper connection. Rust and Bone most certainly suffers from an abundance of plot – especially towards the end – but the performances, script and use of music is strong enough that it had me totally compelled and invested in the characters by the end.

Rust and Bone on the other hand – despite perhaps deserving just as much criticism being levelled at it – succeeded in being really quite moving. The plot concerns the rehabilitation of Marion Cotillard’s Stéphanie, an orca trainer who one day loses her legs during an incident at the marine centre where she works. Reconnecting with bouncer Ali (Matthias Schoenaerts), whom she met at a club before the accident, Stéphanie gradually develops a new place in the world, at first through their casual relationship and later becoming a deeper connection. Rust and Bone most certainly suffers from an abundance of plot – especially towards the end – but the performances, script and use of music is strong enough that it had me totally compelled and invested in the characters by the end.

Perhaps spurred on by the thriller aspects of Argo I found myself craving another dose of Hollywood suspense and watched  The Fugitive (1993) for the first time. Hugely enjoyable and engaging – I kept thinking “what’s going to happen to Harrison?!” -despite better judgement telling me it’ll probably be alright in the end. What I found most interesting was the attention the screenwriters pay to the relationship Gerard (Tommy Lee Jones) has with his deputies. Strangely touching – like a papa bear to his cubs.

The Fugitive (1993) for the first time. Hugely enjoyable and engaging – I kept thinking “what’s going to happen to Harrison?!” -despite better judgement telling me it’ll probably be alright in the end. What I found most interesting was the attention the screenwriters pay to the relationship Gerard (Tommy Lee Jones) has with his deputies. Strangely touching – like a papa bear to his cubs.

The monster movie this week was The Faculty (1998), a film that seeks to satirise the clichés of high school comedies whilst reinforcing them by the final reel. Great to be reminded of all the excellent performances from said faculty; Salma Hayek, Jon Stewart, Bebe Neworth, Piper Laurie, Famke Janssen and Robert Patrick as the creepy coach.

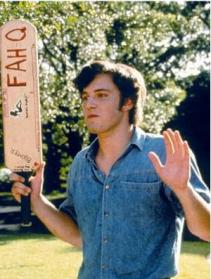

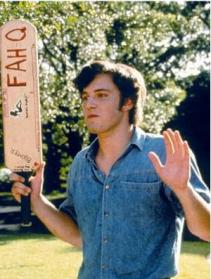

Following that high school treat, and in retrospect probably inspired by Affleck’s cinematic ‘maturity’, I returned to the always excellent Dazed and Confused (1993) in which said director plays bully O’Bannion (with remarkably similar hairstyle to his later Mendez incarnation, minus the beard) – tormenting the new freshmen on the last day of school in 1976.

Following that high school treat, and in retrospect probably inspired by Affleck’s cinematic ‘maturity’, I returned to the always excellent Dazed and Confused (1993) in which said director plays bully O’Bannion (with remarkably similar hairstyle to his later Mendez incarnation, minus the beard) – tormenting the new freshmen on the last day of school in 1976. Linklater’s often dreamy depiction of 1970’s youth benefits from some delightfully awkward performances, notably Wiley Wiggins as Mitch Kramer (Wiggins is also in The Faculty) who relies one too many times on a ruffled brow and hand acting and is all the more charming for it. It’s a shame that so many high school films lean on the same tired plots whilst Linklater’s effort seems effortlessly tremendous nearly twenty years later.

Linklater’s often dreamy depiction of 1970’s youth benefits from some delightfully awkward performances, notably Wiley Wiggins as Mitch Kramer (Wiggins is also in The Faculty) who relies one too many times on a ruffled brow and hand acting and is all the more charming for it. It’s a shame that so many high school films lean on the same tired plots whilst Linklater’s effort seems effortlessly tremendous nearly twenty years later.

Sound it Out buy Jeanie Finlay was a melancholy and empathetic film concerning one of the last independent record shops in the UK, the titular establishment situated in Stockton, Teesside in the North East of England. Finlay interviews the owners and regular customers of the store – which for those singled out – seems to form, in turns, a lifeline, an addiction and an essential component of their sense of identity.  I felt that Finlay didn’t offer much in terms of the factual history of the area, preferring to concentrate on the testimonies of her interviewees – which at times results in contrived scenes involving them lip-syncing their favourite tunes – a misstep that turns fully rounded people, into an object of amusement.

I felt that Finlay didn’t offer much in terms of the factual history of the area, preferring to concentrate on the testimonies of her interviewees – which at times results in contrived scenes involving them lip-syncing their favourite tunes – a misstep that turns fully rounded people, into an object of amusement.

Friday night saw the first in a selection of Chantal Akerman films at the French Film Festival, hosted by Edinburgh Filmhouse, which kicked off with her latest, Almayer’s Folly (2011). Adapted from the Joseph Conrad novel of the same name, the film concerns the fraught relationship between a white, European trader (Stanislas Merhar as Almayer) and his mixed race daughter, Nina (Aurora Marion) living in Malaysia.  Almayer’s ineffectual nature and clouded judgement make him a frustrating character to watch, but is an essential aspect of the overall claustrophobia that develops as a central concern of the film. Almost every scene features water, whether it’s the characters wading through sodden ground, travelling by boat or getting soaked by the rain – giving the sense of their inability to escape their circumstances, and the obstacles that face them whenever they try to affect change.

Almayer’s ineffectual nature and clouded judgement make him a frustrating character to watch, but is an essential aspect of the overall claustrophobia that develops as a central concern of the film. Almost every scene features water, whether it’s the characters wading through sodden ground, travelling by boat or getting soaked by the rain – giving the sense of their inability to escape their circumstances, and the obstacles that face them whenever they try to affect change.

Saturday saw the second of three Akerman films, Meetings with Anna (1978), an autobiographically inspired story of a filmmaker’s journey from Germany to Paris, and her interactions with family, strangers and friends along the way. A masterful portrait of a non-conforming female that gradually reveals social, political and personal tensions between Anna and those she encounters.

Saturday saw the second of three Akerman films, Meetings with Anna (1978), an autobiographically inspired story of a filmmaker’s journey from Germany to Paris, and her interactions with family, strangers and friends along the way. A masterful portrait of a non-conforming female that gradually reveals social, political and personal tensions between Anna and those she encounters.

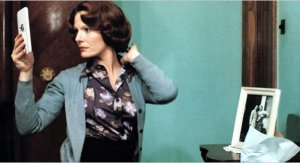

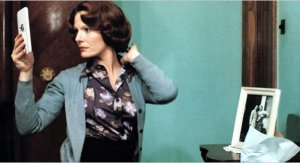

Finally, the week’s viewing came to an end with the magnificent Jeanne Dielmann, 23 Quai de Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), Chantal Akerman’s most celebrated film. This three hour and twenty minute tale of three days in the life of the titular Belgian housewife uses mainly static interior shots to describe Jeanne’s routine (and disruption of that routine) consisting of domestic chores and highly controlled prostitution. The vigorous formalism of each still shot, in which we see Jeanne engage in such banal tasks as making coffee or prepare the evening meal mean that whenever a new camera angle is used, it’s the equivalent of an explosion in a Hollywood action film – confounding out expectations of what the plot has been until that point. Jeanne’s unravelling, presumably triggered by a letter from her sister and her son’s (sudden?) interest in his parent’s relationship and the strangeness of sex, is perhaps too extreme to be wholly believable but nonetheless this is still one of the most astonishing pieces of cinema I’ve ever had the pleasure of watching.

Finally, the week’s viewing came to an end with the magnificent Jeanne Dielmann, 23 Quai de Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), Chantal Akerman’s most celebrated film. This three hour and twenty minute tale of three days in the life of the titular Belgian housewife uses mainly static interior shots to describe Jeanne’s routine (and disruption of that routine) consisting of domestic chores and highly controlled prostitution. The vigorous formalism of each still shot, in which we see Jeanne engage in such banal tasks as making coffee or prepare the evening meal mean that whenever a new camera angle is used, it’s the equivalent of an explosion in a Hollywood action film – confounding out expectations of what the plot has been until that point. Jeanne’s unravelling, presumably triggered by a letter from her sister and her son’s (sudden?) interest in his parent’s relationship and the strangeness of sex, is perhaps too extreme to be wholly believable but nonetheless this is still one of the most astonishing pieces of cinema I’ve ever had the pleasure of watching.

Jeanne Dielmann was voted 36th Greatest Film of All Time in Sight & Sound’s once a decade poll, and Chantal Akerman is the only female director in the top 100 films.

Despite 2012 being the year Alfred Hitchcock was consistently celebrated; with a retrospective at the BFI in London, including restorations of his early, silent films – the ‘Rescue the Hitchcock 9’ project, which was part of the Cultural Olympiad; and two films The Girl (Julian Jarrold) and Hitchcock (Sacha Gervasi, released on 8 February), I still didn’t manage to catch up on the great director’s entire work. So, to continue my efforts The Trouble with Harry (1955) was this week’s Hitch selection. Set in a quiet and picturesque New England town, the film opens with Captain Albert Wiles (Edmund Gwenn) talking to himself as he seeks the victim of a morning’s hunt, whilst young Arnie (Jerry Mathers) plays alone nearby. The Captain’s chatter can be taken as an idiosyncrasy of the character or more likely – a self conscious way to guide the viewer as to his thoughts

Despite 2012 being the year Alfred Hitchcock was consistently celebrated; with a retrospective at the BFI in London, including restorations of his early, silent films – the ‘Rescue the Hitchcock 9’ project, which was part of the Cultural Olympiad; and two films The Girl (Julian Jarrold) and Hitchcock (Sacha Gervasi, released on 8 February), I still didn’t manage to catch up on the great director’s entire work. So, to continue my efforts The Trouble with Harry (1955) was this week’s Hitch selection. Set in a quiet and picturesque New England town, the film opens with Captain Albert Wiles (Edmund Gwenn) talking to himself as he seeks the victim of a morning’s hunt, whilst young Arnie (Jerry Mathers) plays alone nearby. The Captain’s chatter can be taken as an idiosyncrasy of the character or more likely – a self conscious way to guide the viewer as to his thoughts  and motivations as he goes about trying to decide what to do with Harry’s corpse.

and motivations as he goes about trying to decide what to do with Harry’s corpse.