Second Run DVD’s latest release, The Czechoslovak New Wave: A Collection is a perfect introduction to this period of creative brilliance, including as it does, three excellent and diverse works. Diamonds of the Night (1964) by Jan Nemec was adapted from Arnost Lustig’s novella, Darkness Casts No Shadow, and strips out dialogue and contextual information to a bare minimum so that the film’s simple plot becomes an absorbing and horrific survival tale. Following the struggle to remain both alive and free by two young men; who have escaped a German train bound for a Nazi concentration camp during World War II, Diamonds of the Night opens in the thick of a chase, as the escapees flee armed men, by scrambling and pushing onward through the vegetation of the forest floor. The camera follows them in wide shot and gradually zooms closer as they trip and stumble on uneven terrain. It’s a truly remarkable opening, establishing quickly that the film’s formal aesthetic will be as economical as its protagonist’s basic endeavour – to survive.

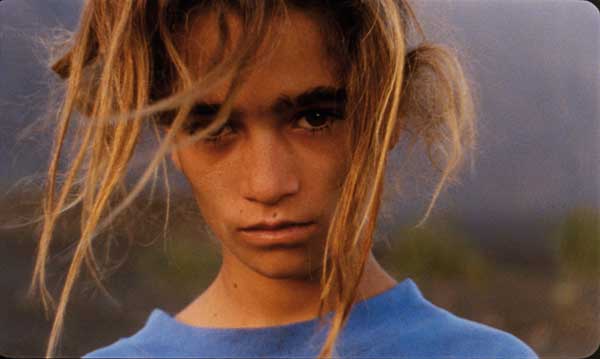

Diamonds of the Night (1964) by Jan Nemec was adapted from Arnost Lustig’s novella, Darkness Casts No Shadow, and strips out dialogue and contextual information to a bare minimum so that the film’s simple plot becomes an absorbing and horrific survival tale. Following the struggle to remain both alive and free by two young men; who have escaped a German train bound for a Nazi concentration camp during World War II, Diamonds of the Night opens in the thick of a chase, as the escapees flee armed men, by scrambling and pushing onward through the vegetation of the forest floor. The camera follows them in wide shot and gradually zooms closer as they trip and stumble on uneven terrain. It’s a truly remarkable opening, establishing quickly that the film’s formal aesthetic will be as economical as its protagonist’s basic endeavour – to survive.

There’s also a surrealist aspect to the editing – clearly influenced by the likes of Luis Buñuel – that shows ants crawling over hands and editing that cuts between the boys current struggle and what is presumably their remembered past – the initial flee and life before capture. A great deal of this is silent, or at least uncluttered by the presence of a musical score, giving the sound of frightened breathing, or a clocks chimes, or footsteps, a rhythm of its own. The horror of the situation is enhanced by the fact that these young men’s pursuers are elderly men – all crumpled faces and hunched backs. This didn’t go unnoticed by Michael Brooke, whose essay about the film accompanies the DVD release and notes the incongruity of the old having better survival chances than the young.

In contrast, this three-film collection includes the delight that is Ivan Passer’s Intimate Lighting, (1965)the story of two musician friends, Bambas (Karel Blazek) and Petr (Zdenek Bezusek) who took different career paths, and spend the weekend at the formers’ country home. Petr brings along his girlfriend Stepa (Vera Kresadlova), who delights in Bambas’ children and takes advice on slimming from his mother.

In contrast, this three-film collection includes the delight that is Ivan Passer’s Intimate Lighting, (1965)the story of two musician friends, Bambas (Karel Blazek) and Petr (Zdenek Bezusek) who took different career paths, and spend the weekend at the formers’ country home. Petr brings along his girlfriend Stepa (Vera Kresadlova), who delights in Bambas’ children and takes advice on slimming from his mother.

The action in the film is actually less action – in the dramatic sense – than the naturalism of an idle weekend’s encounters and moments. Bambas, who plays at the local music school, and Petr, who tours with an orchestra, share stories and get to know the similarities and differences in how their lives are playing out.

How they are playing out is complemented – as would be expected – by music, which represents shifts in mood throughout the film; the solemnity of a funeral chorus, the combined melancholia and forced jollity of the wake, a comedic quartet rehearsal stinted by elderly hands. There’s a wonderful sense of wit that comes from the film’s rhythm and absurdity – an awkward eggnog toast that becomes funnier the longer the shot is held; a late night, drunken escapade accompanied by another Strauss waltz.

All this makes for a fresh and thoughtful film that combines the character’s pathos with daily joy to result in a truly enjoyable and poignant must-see.

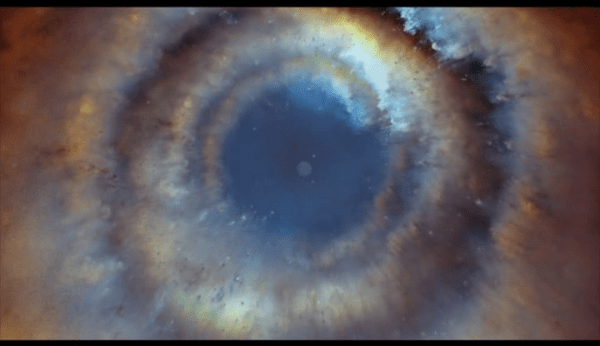

The third film in this excellent box set is the unnerving and occasionally terrifying The Cremator (1968)by Juraj Herz, a film that – like Intimate Lighting uses music brilliantly to convey the films tone, and as with Diamonds of the Night utilises a surrealist montage of images. Unlike that earlier film however, Herz takes the surrealism further – the opening credits alone use animation techniques familiar from the work of Jan Svankmayer – whom Herz studied puppetry alongside.

The third film in this excellent box set is the unnerving and occasionally terrifying The Cremator (1968)by Juraj Herz, a film that – like Intimate Lighting uses music brilliantly to convey the films tone, and as with Diamonds of the Night utilises a surrealist montage of images. Unlike that earlier film however, Herz takes the surrealism further – the opening credits alone use animation techniques familiar from the work of Jan Svankmayer – whom Herz studied puppetry alongside.

The Cremator concerns a man of the titular profession; Karel Kopfrikingl (Rudolf Hrusinsky) living in Prague during the Nazi occupation, with his ‘perfect’ family in his well furnished home. Karel is inspired by the political climate of the time to improve and refine his life, which leads to the most terrible inevitability. The hypnotic, heavenly chorus, appearing throughout the score, gives the impression that – beyond his professional activity – Karel aspires toward his world as a kind of faultless afterlife. He’s a precise, fiercely vigilant man; one who, it turns out is susceptible to the ideals of others, even if their actions are more extreme than his own.

Special features accompanying the film include an introduction by the Brothers Quay, who enthuse eloquently about the unique vision of Herz, providing an appreciated cultural and historical context for such astonishing filmmaking.

If like me, you desire to know more about the Czech New Wave – this is another illuminating and welcome collection from Second Run DVD, who prove their impeccable taste time and again.

You can read a review of another great box set here