Ostensibly a home-movie portrait, Papirosen (the title refers to a Yiddish song about an orphaned boy who sells cigarettes to survive) becomes so much more than that. Carefully interweaving his own footage covering a ten-year period in the life of his Argentine Jewish family with that of Super 8 recordings stretching back to the 1960’s, Gastón Solnicki’s film reveals the intricacies of familial ties. Beginning with the birth of his nephew, Mateo, and documenting the small and big moments in his family members’ lives, Solnicki trains his camera on his family with so much love we sense that he doesn’t ever want to turn it off.

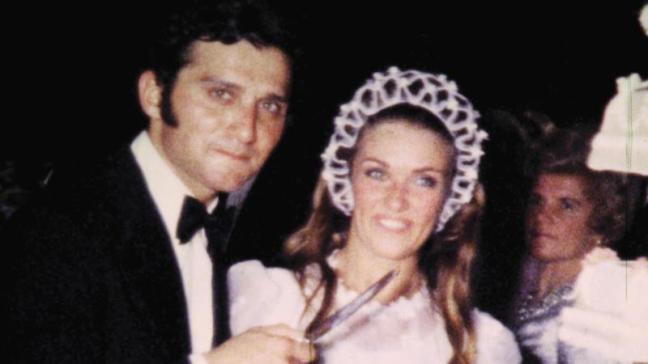

We are first introduced to the family members while they holiday in Florida: sister Yanina, mother Mirta, and, at the centre of it all, father Victor. A patriarch in every sense of the word, Victor exudes the air of a charismatic protector and stern authoritarian, one who dotes on his grandchildren and doesn’t mind scolding his daughter for her suitcase packing skills. Gradually Gastón’s continued presence (whether welcomed or not by his family) exposes the deep-rooted emotional scars left from the family’s experience as part of the expulsion of Jews from Poland during World War II. Victor’s mother, Pola, provides a voice-over that opens the film and continues at points throughout. At one point she wearily describes the outbreak of war: “After about half a year the Germans gathered people to take to the concentration camps… Treblinka, Auschwitz and many more I can’t remember. I was 16 back then.”

In one of many other arrestingly poignant scenes, a friend of Victor’s father breaks into song during a meal at a diner, provoking instant tears from the otherwise unflappable Victor. At this outpouring of memory and emotion, Mirta declares that her husband needs psychotherapy, if only to help him get over the death of his father, whom he says died of sadness.

Although the family gather for a formal dinner towards the end of the film, this is not the moment of catharsis that a more conventional documentary might build towards. Demonstrating himself as a sensitive and thoughtful director, Solnicki chooses a cyclical route, closing the film with a quiet scene between Victor and Mateo. Seen at the film’s opening in wide shot, and now in close-up on a chairlift heading upwards to snowy peaks, Victor sings to his grandson, just as his father did for him: “He is our Father, He is our King. Our Father Saviour.”

Papirosen was given a special mention by the International Feature Competition Jury at the Edinburgh International Film Festival 2012. The jury was headed by Elliott Gould and also included Lav Diaz and Julietta Sichel.

This text originally appeared in the EIFF Catalogue.